Now why do we call the EPS file format, more formally referred to as encapsulated postscript, evil? Because, with EPS, we are never quite sure what we are going to get. The format has less than consistent support for transparency advanced clipping masks and spot color. In addition, certain export settings resemble to the old style “flattened” version of digital art, such as the PDFX1/a.

Let’s take a look at how wacky this can get by revisiting our sample art from a previous posting. Notice that the same spot color is used on several different objects. Also, take note of the white portion of the BPI logo; it employs a feature called a drop shadow which overlays the custom Reflex Blue spot color.

Now, let’s make an EPS from Adobe Illustrator with the export compatibility set for CS3. First, let’s take a look at our initial result (Banner_Art_eps).

Notice that the layer structure is intact. It is unchanged from the Illustrator source file. Now, let’s examine the art in outline view (see Banner_Art_eps_Outlines).

Notice the complete absence of slices. As you can see in the Banner_Art_eps_LiveScripts screenshot below, the Illustrator scripts for fills and drop shadows are still active. A number of newer RIPs (Raster Image Processors) can read these appearance scripts and correctly interpret them.

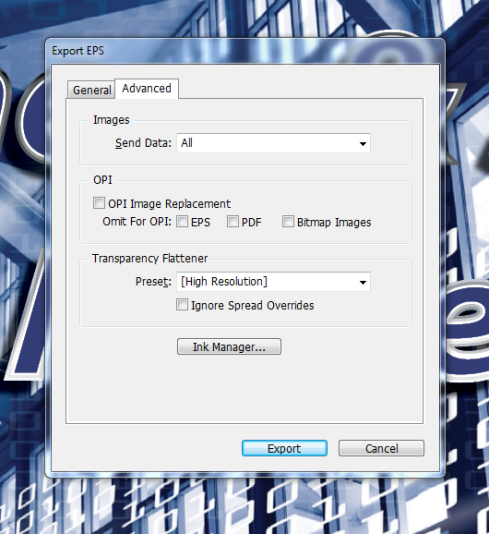

So where’s the problem? Let’s toss a bomb into the mix. Let’s place the same art in InDesign and export to EPS and use the highest quality settings available (see InDesign_Export_eps screenshot).

Let’s take a look at the results in outline view (see InDesign_eps_Outlines).

Instead of a digital file made up of vector objects and live scripts, we now have a mixed bag of vector and raster objects. We also have a pretty obvious slicing error. But wait, it gets worse! Take a look at the color values in the logo (see Color_Error1 screenshot below).

That’s not the only potential color problem. Take a look at the cmyk values of the image slice in the logo (see Color_Error2 at left). That particular slice butts up to the vector object with the  original spot color value (see Color_Error3). Now things are getting really complicated. In the large format world, a RIP

original spot color value (see Color_Error3). Now things are getting really complicated. In the large format world, a RIP calculates color values and it usually calculates a spot color, vector object in LAB. However, a raster image, like the one in Color_Error3, will be calculated in cmyk. Print this file and you will have two very different shades of blue piled next to each other. Furthermore, print this file and you better be ready to do this job over.

calculates color values and it usually calculates a spot color, vector object in LAB. However, a raster image, like the one in Color_Error3, will be calculated in cmyk. Print this file and you will have two very different shades of blue piled next to each other. Furthermore, print this file and you better be ready to do this job over.

Frankly, the future of the EPS file format is solidly in the past. EPS is rapidly becoming an outdated file format which is being replaced by PDF just like PostScript itself is also being phased out and replaced by PDF. Check out what Dov Isaacs from Adobe said in a discussion on a Print Planet forum about the future of PostScript:

“ …Adobe will continue to support EPS as a legacy graphics format for import of non-color managed, opaque graphical data into Adobe applications (such as InDesign and Illustrator). Although we certainly do not recommend that new graphical content be stored in EPS format (except to satisfy the need to import data into page layout programs that aren’t quite PDF-centric), our user base should feel comfortable that there is no need to worry about a need to convert their very sizable libraries of EPS-based graphic assets.”

When a principal scientist with Adobe employs the phrase “legacy graphics format,” it’s time to move on.

Flattening and transparency are pretty confusing subjects. If you’re still curious, or just plain lost in the woods over flattening and transparency, check out the online tutorial below for more information.

http://vector.tutsplus.com/articles/help-with-selling-vector-stock-in-eps10-format